Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Metastatic prostate cancer refers to cancer that has spread beyond the prostate to other parts of the body. Prostate cancer most commonly spreads to bones and lymph nodes, and sometimes to other organs such as the liver or lungs. You may also hear this described as advanced prostate cancer. Patients can have metastatic prostate cancer at the time of initial diagnosis, or they may have metastases as a recurrence of their disease, years after treatment for localized prostate cancer.

Aggressive prostate cancers usually warrant imaging scans to determine the presence of metastatic disease. In the U.S., this is most commonly done with a computed tomography (CT) scan or an MRI and a bone scan. Newer and more sensitive imaging technologies include molecular positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, such PSMA PET.

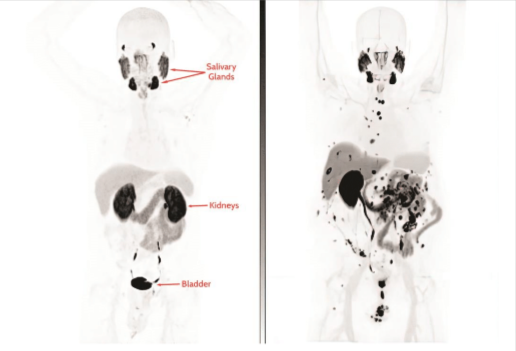

Imaging Scans are Used to Evaluate for Metastasis

Left panel: A patient’s PSMA PET scan shows no metastases.

Right panel: A patient’s PSMA PET scan shows extensive metastases to the bones, lymph nodes, and lining of the abdomen (peritoneum). Note that uptake to the salivary glands is normal, since PSMA is expressed there. Also note that the contrast is emptied through the kidneys and bladder, and this is also normal.

Treatment of metastatic prostate cancer is generally based on whether its growth can be slowed or stopped with hormone therapy. Testosterone (an androgen hormone) is the“fuel” that makes prostate cancer cells grow. Hormone therapy lowers testosterone, cutting off the“fuel supply” for prostate cancer cells

- Metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) can be controlled with hormone therapy.

- Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) means that prostate cancer cells have gained the ability to grow in the low-testosterone environment and can no longer be controlled with standard hormone therapy.

Last Reviewed: 12/2023