Are you at higher risk of getting aggressive prostate cancer? Results of two studies say the answer may be staring you right in the face. Actually, a little higher: in the hairline.

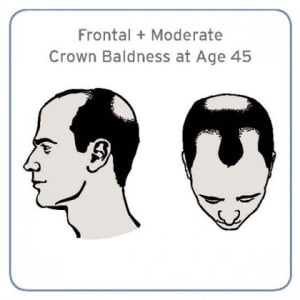

One study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, shows that men who have a certain pattern of early male pattern balding – specifically, loss of hair at both the forehead and at the crown – have a 40-percent higher risk of developing aggressive cancer. In this study, investigators at the National Cancer Institute, George Washington University, and the Cancer Prevention Institute of California looked at 39,070 men who had taken part in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Screening Trial, and asked the question, what did their hair look like at age 45?

The investigators were looking for an association between hair loss and prostate cancer. They didn’t find a link between every balding guy and prostate cancer. They also didn’t find a link between this particular pattern of hair loss, called “frontal plus moderate vertex baldness,” and overall prostate cancer risk, or the risk of developing the slow-growing kind of cancer that may not need to be treated.

The investigators were looking for an association between hair loss and prostate cancer. They didn’t find a link between every balding guy and prostate cancer. They also didn’t find a link between this particular pattern of hair loss, called “frontal plus moderate vertex baldness,” and overall prostate cancer risk, or the risk of developing the slow-growing kind of cancer that may not need to be treated.

Instead what they found was more worrisome, and important, and something that should make a lot of people – family doctors, internists, urologists, and men with this pattern of hair loss – take notice: frontal plus moderate vertex baldness was “significantly associated with an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer.” This is the kind of cancer that needs to be treated, and the kind of cancer that can be lethal.

What’s happening here? What connection is there between the hair follicles on the forehead and top of the head to the prostate – specifically, to the prostate’s peripheral zone, the trouble spot where cancer develops? Genetic changes. In male pattern baldness, men don’t actually stop making hair. But the hair they do make morphs from hair that can grow long and luxuriantly into hard-to-see, tiny, baby-fine hair. From adult hair, in effect, into the kind of hair we all have as infants.

Scientists are not positive which genes are involved, but they do have a clue. If this were a crime scene, we might say police have no suspects, but they are interviewing a person of interest. In this case, the faulty gene of interest is one called Maspin. It is a tumor suppressor gene, designed to keep cell growth and division orderly, and to discourage the rampant, out-of-control growth that happens in cancer.

Mice, when the Maspin gene is disabled, develop a bald spot; they also get early prostate cancer. Another key thing happens: “When the Maspin gene is knocked out,” says medical oncologist Jonathan Simons, M.D., CEO of the Prostate Cancer Foundation, “it allows cancer cells to move around – to migrate – and also to become more vicious, just like metastatic, high Gleason-grade cancer in men. If we can figure out the basic biology here, we might be able not only to prevent prostate cancer in these men, but to reverse male pattern baldness.” Clearly, there is a pathway that scientists have yet to discover. “The hunt is on. Whether the Maspin gene ultimately turns out to be the cause, this research is going to give us an idea what’s going on with these men, and it involves genes shared by hair follicles that have growth cycles, and prostate cancer cells that cycle. ”

There is precedent for such a physical characteristic to be linked to a health problem. People who have freckles on their lips also are more likely to get colon cancer; this is called Putz-Jaeger Syndrome. In dogs, the same gene that causes deafness in some Dalmations also gives them blue eyes. But never before have we known about such a link in prostate cancer – and such an easy-to-notice one, at that.

Changing the Profile of Who’s at Higher Risk

Right now, men known to be at higher risk for prostate cancer are:

- Men with a family history of prostate cancer, and of other types of cancer.

- Men of African descent.

- To a lesser extent, men who smoke and men who are overweight.

It looks like we need to expand this category to include men with frontal plus moderate vertex baldness. “Out of 143 forms of adult cancer,” says Simons, “prostate cancer is the only cancer where a hair feature that can be evident from across the room is associated with cancer risk. There’s nothing else in oncology like that kind of association.”

A very important note: We’re talking about men who develop this baldness in their twenties and thirties. More studies are needed to figure out the specifics of when prostate cancer screening for these men needs to start, but it very well may need to begin when men are in their thirties. This is because the men with this pattern of baldness who do develop prostate cancer – and not all of them do, for reasons we don’t understand, perhaps involving such environmental factors as diet, weight, and exercise – have higher Gleason-grade cancer.

What about that other study we mentioned? It was a Canadian study, and much smaller, but the results were similarly striking. University of Toronto scientists have determined that early male pattern baldness represents a “strong and independent risk factor” for prostate cancer – and the more baldness, the higher the risk of cancer.

In the study, published in the Canadian Urological Association Journal, a research team looked at medical records and male pattern baldness in nearly 400 men who came to Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto for prostate biopsy. (This means that either they had a rising PSA or concerning findings from other tests, or a doctor had felt a suspicious area during a rectal exam.) They asked these men to self-report their “degree of baldness” at age 30; then, their hairlines were evaluated on the Norwood scale, which classifies patterns of hair loss. Note: Self-reporting, scientifically speaking, has room for error. Men might not have noticed exactly what was happening with their hairline; they may remember it as rosier than it actually was, or the opposite – there may have been some hair-loss denial happening.

Still, the results were striking: The investigators found that men who had a greater extent of baldness – receding hair in the front, and a bald spot on top – had a higher risk of getting prostate cancer. Dr. Neil Fleisher, who co-authored the study, said men who develop baldness early and who get a lot of it “are particularly at risk.”

Men with a higher degree of baldness on the Norwood scale were three times as likely to be diagnosed with higher-grade prostate cancer, the kind that really needs to be treated.

Findings from both studies may soon mean that when men go to the doctor for regular check-ups, their doctor may take a picture of their hairline – and if the hairline starts to change, it may be time to start prostate cancer screening.

If you are a young guy who is losing his hair and you’re worried about prostate cancer, don’t despair. The hopeful news here is that you may have what so many scientists have been looking for – a clear sign, visible years before you might otherwise find out, that you might be at higher risk of prostate cancer. Which means that you also have an excellent chance of having it detected in time to cure it before it ever becomes a problem.