How BAT Works

Several years ago, medical oncologist Samuel Denmeade, M.D., Co-Director of the Johns Hopkins Prostate Cancer Program, and colleagues came up with a remarkable concept for attacking prostate cancer: alternating ADT with high-dose testosterone.

Patients have asked Denmeade if this treatment, called Bipolar Androgen Therapy (BAT), could be used as initial therapy for metastatic cancer instead of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or even as primary therapy instead of prostatectomy or radiation. “No and no,” says Denmeade. “BAT was designed to work against castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).”

In CRPC, the cancer’s environment is significantly different than it is in earlier- stage cancer. As CRPC cells learn to adapt to the lack of testosterone with ADT, “they crank up the androgen receptor (AR) to high levels,” and make themselves comfortable in the new environment. But with high levels of AR, the cancer cells are sitting ducks, vulnerable to the shotgun blast of a hefty dose of testosterone. “Flooding the prostate cancer cell with testosterone gums up the works: suddenly, the cancer cells have to deal with too much androgen (male hormone) bound to the receptor. This disrupts their ability to divide. They either stop growing or die.”

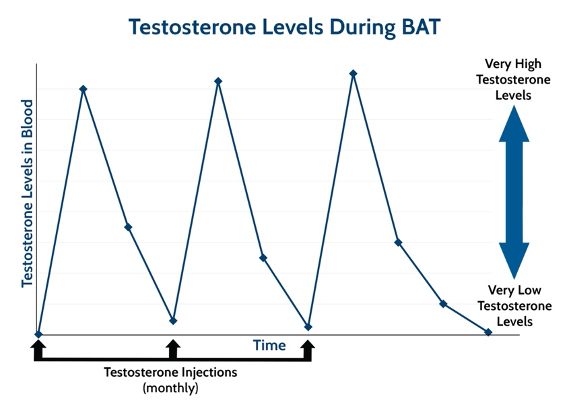

It’s all about creating chaos in the environment, so the cancer cells can’t thrive, and timing is critical. “ADT initially works because prostate cancer cells are suddenly deprived of testosterone, and most of them can’t survive this shock.” Cancer cells die by the thousands, PSA plummets, imaging scans show cancer shrinking, and symptoms improve. But prostate cancer, like the Road Runner, is elusive. Over time, the hardy band of surviving cells regroups, adapts to living in the low-testosterone environment, and begins to grow again. “BAT is a similar type of hormone shock – just in the opposite direction,” says Denmeade. “A key feature of BAT is the rapid change from a very high- to low-testosterone level.” Men remain on ADT, and receive monthly shots of high-dose testosterone, which gradually fades, then bumps back up again with the next monthly shot. That’s the bipolar part of Bipolar Androgen Therapy (see Figure). “The repeated shocks of BAT cycling don’t give the cancer cells time to adapt, “because the underlying environment is always changing.”

So far, in four clinical trials at Hopkins, Denmeade and colleagues have given BAT to about 350 men with CRPC, most of whom have also received enzalutamide (Xtandi), abiraterone (Zytiga), or both. For men with CRPC whose disease is worsening on ADT or on AR-blocking drugs like enzalutamide or abiraterone, BAT is highly promising. In the recent TRANSFORMER study, “we compared BAT head-to-head with enzalutamide” in patients with CRPC who had progressed on ADT and abiraterone. “It was kind of a weird study, comparing a drug to its exact opposite: an androgen vs. an anti-androgen. I don’t know if anybody’s ever done a study like that. To our amazement, BAT and enzalutamide were nearly identical in terms of their effect.” PSA levels dropped in about 25 percent of men on either treatment, and for both treatments, the response lasted about six months.

However, the real difference between the treatment arms was seen after cross-over – when men on BAT were switched to enzalutamide or vice versa. “If we gave BAT first and then enzalutamide, almost 80 percent responded, and the response lasted almost a year. That’s quite an improvement in the rate of response and duration.” Among patients who received enzalutamide first, followed by BAT, the response rate to enzalutamide was only 23 percent.

This begs the question: Why stop after one round of BAT then enzalutamide? Why not just keep going? “We should be able to cycle back and forth over and over again,” says Denmeade. The STEP-UP trial, of 150 patients at Johns Hopkins and eight other centers nationwide, is looking at just this, “sequencing androgen and anti-androgen. There are two BAT treatment arms: in one, the patients just switch every two months – two months of testosterone, two months of enzalutamide. In the other, the men stay on testosterone until their PSA goes up, and then switch to enzalutamide, and stay on that until their PSA goes up,” then repeat. Cancer response is also monitored by regular CT and bone scans. Patients stop treatment if scans show cancer progression.

The BAT studies thus far have been small, Denmeade says. “We need a big phase 3 study; we’ve just been nipping at the edges.” For now, BAT remains investigational; positive results from larger randomized trials are needed for it to be considered standard of care. While not a cure for advanced prostate cancer, BAT may become an option for extending life and, importantly, improving quality of life.

Note: BAT is not recommended for men with symptomatic bone pain from metastatic prostate cancer, because it can make that pain worse. “This pain increase occurs within hours of testosterone injection, and resolves as testosterone levels in the blood decline over the first cycle of BAT,” says Denmeade. “The worsening pain is not due to rapid growth of prostate cancer, but more likely to testosterone-stimulated release of inflammatory factors.”