Over the last two decades, the death rate from prostate cancer has declined more than 50%. In itself, this is a monumental accomplishment that can be attributed to a constellation of factors including earlier detection, improved treatments, and better access to care—especially among underserved communities. But this large-scale trend also raises an important question: what, if anything, has changed for the individual patient on his prostate cancer journey?

Of course, just as each prostate tumor is biologically unique, so too each patient’s journey represents a singular experience. But how does each generation of advances in medicine and technology translate to the patient experience, beyond these broader trends in survival? Moreover, what do these advances mean for men and their families today, and how is this different from the experience of their fathers and grandfathers before them? And finally, what does the future hold?

To delve deeper into the prostate cancer patient experience over the long term, PCF sat down with Mary-Ellen Taplin, MD, Director of Clinical Research, Lank Center for Genitourinary Oncology Institute, Physician and Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; and PCF’s Medical Director Stuart Holden, MD, Health Sciences Clinical Professor of Urology and Associate Director, UCLA Institute of Urologic Oncology.

Together, Drs. Holden and Taplin have a combined 70 years of experience in urologic oncology treating prostate cancer patients at all stage of disease. They have both seen the trajectory of how medical trends and technological innovations have inexorably and irreversibly altered the way men are diagnosed, treated, and managed.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the years of training required to become a urologic oncologist. After graduating from medical school in 1968, Dr. Holden completed two years of surgery training, followed by two years in the military. He began his training in urology in 1972 and completed it at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, having been attracted to the field for its complexity and diversity of cases. “Urology is a fantastic field that encompasses everything: children, the elderly, immunology, and cancer.” said Dr. Holden. “It’s one of the few fields where you can do both medicine and surgery to take care of people. Many of the most seminal discoveries in oncology were introduced to treat urological cancers.”

Dr. Taplin began her research career in cancer immunology in the early 1990s, but began working on prostate cancer (on the androgen receptor) in the laboratory of Dr. Steven Balk. By 1995 she and the team had discovered interesting androgen receptor mutations that became the basis for a New England Journal of Medicine article advancing knowledge in prostate cancer treatment resistance.

The Early Days

When he began practicing urology in the early 1970s, prostate cancer represented only about 10% of Dr. Holden’s practice. The men who did have prostate cancer were diagnosed in one of three ways: following a transurethral prostatectomy (for the treatment of an enlarged prostate), when a patient presented with metastatic disease (e.g., pain from bone lesions) or during a digital rectal exam, which is part of routine exams today.

In the early days, men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer were treated with surgery, radiation, or “watchful waiting,” now known as active surveillance. But none of these techniques was particularly sophisticated, and there was no way to properly stage the cancer.

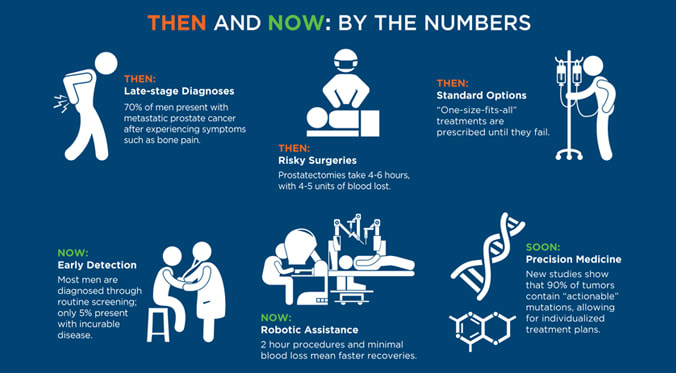

Surgery in particular suffered from a lack of knowledge and technique, often to the detriment of the patient. While generally successful in removing the cancerous prostate, surgical procedures were invasive and dangerous, and with a multitude of after effects. “In the old days,” said Dr. Holden, “the operation would take 4-6 hours, and the patient would lose 4-5 units of blood. He would then be hospitalized from anywhere from 10 days to two weeks. Nerve sparing techniques were virtually nonexistent, so men undergoing a radical prostatectomy were guaranteed a complete loss of sexual function, as well as a 5-8% chance of incontinence.” But, as Dr. Holden emphasizes, despite the high complication rate, many patients were rendered cancer-free.

Prostate Cancer Treatment - Then and Now: By the Numbers

It wasn’t until the 1980s that Dr. Patrick Walsh pioneered a nerve-sparing technique that has become the gold standard for prostate removal. While the “open” operation remained risky for men, especially those of an advanced age, patients were finally afforded a chance to resume a normal, active life following surgery.

The Dawn of the PSA Age

Unfortunately, a general lack of available screening methods meant that by the time many of these men arrived at Dr. Holden’s office, their cancer had advanced beyond the point of cure. This all changed with the introduction of the PSA test in the late 1980s, which led to an explosion of diagnoses and forever changed the face of urology in the United States.

Almost overnight, Dr. Holden’s practice skyrocketed from 10% prostate cancer to a staggering 80%. More impressively, the number of men who presented beyond a curable stage dropped to 5% from an astounding 70%. Clearly the PSA test was something of significance.

These initial results prompted a major push among urologic oncologists to make people aware of prostate cancer and to get a PSA test if appropriate. “Routine screening was a product of the PSA era,” said Dr. Taplin. “If you can feel a tumor during a DRE, generally the cancer is at a later stage. In many ways the PSA test changed all of that.”

The PCF Effect

Despite the many advances that have been made in treating localized prostate cancer, which is now 100% treatable if detected early, roughly 30% of patients will have a poor outcome. PCF was founded precisely for these men, whose aggressive tumors will recur, progress, and metastasize, and whose disease still manages to outsmart even the most sophisticated of therapies.

PCF also played a critical role in driving awareness for prostate cancer during the early years of the PSA era, and these efforts likely contributed to the significant decline in the death rate over the last 20 years. Dr. Holden recalls traveling to Washington, DC, in 1994 with PCF Founder and Chairman Mike Milken and the Reverend Rosey Grier. The trio parked a truck outside of Congress to perform prostate cancer screenings on the National Mall. It was these sorts of guerilla tactics that elevated public awareness of prostate cancer to a level of national discourse.

“The initial treatment options of surgery and radiation have improved and we are more accurate at cancer risk assessment to direct therapy,” said Dr. Taplin. “Radiation is more exact, whereas it used to be crude. With 3D technology and brachytherapy, there are fewer side effects and cure rates are higher.” Research has specifically shown that combining radiation with hormones provides substantial benefits to patients, with a rate of cure that is equal to that of surgery.

For another example, contrast the risk-laden scenario of yesterday’s “open” radical prostatectomies with today’s advanced surgical methods. The “robotic revolution,” which PCF funded in early clinical research in the early 2000s, pioneered a minimally invasive approach to this complex surgery. Today’s so-called “robotic” prostatectomies are performed by a computer-assisted device that is controlled by a surgeon, giving the surgeon better vision and dexterity, allowing the procedure to be performed with greater precision than ever.

Utilizing the latest in robotic technologies, surgery for prostate cancer now takes 2-3 hours with negligible blood loss, and hospital stays have been reduced to 24 hours. Most importantly, robotic prostatectomies carry upwards of 80% nerve-sparing potential, with only a 1-2% risk of serious incontinence. This means that men diagnosed with prostate cancer today can resume a normal lifestyle in ways that were impossible for their predecessors.

“In addition,” said Dr. Holden, “physicians and surgeons have better education and training, and now, everyone in a urologic oncology fellowship will train with robots. However, in terms of oncological outcome, the results are the same. But the recovery and quality of life following treatment are better, as is the patient experience in general.”

A major advancement has been improvements in risk stratification, says Dr. Taplin. The ability to identify who is at greatest risk of aggressive disease is a critical step in both curing disease when possible and in improving life after treatment.

Men and their families are more involved in the treatment process than ever before, making the prostate cancer journey a collective family affair. “Men are very engaged these days, more so than in the early 1990s when I started practicing GU oncology. There is so much more information and people are more aware of their choices and they take time to assess these choices,” said Dr. Taplin. “There is much more shared decision making and a focus on education and individualized treatment plans.”

The information available to men with prostate cancer has led to changes in the doctor-patient dynamic. “It’s very important to me to interact with patients, though the Internet has made that more demanding,” said Dr. Holden, referring to the wealth of materials now available online. “I see my job now as a tour guide. I help patients understand what their options are to get the best possible outcome.”

PCF is actively recruiting new research ideas from 19 countries to improve the far earlier detection of aggressive prostate cancer. Much of this effort is in supporting research on the role of genes that turn a normal prostate cell into a cancer cell.

What Does the Future Hold?

Dr. Taplin is adamant: PSA testing is useful while we await additional new technologies to catch prostate cancers even earlier. “Patients who are at risk should be screened. The problem with no screening is that it’s bad for men who are most at risk,” she says. Dr. Holden concurs. “The PSA test is not perfect, but it is the best one we have. To throw out the test would risk going back to the old days, and we cannot turn the clock back,” he says.

Now well into his fifth decade as a urologic oncologist, Dr. Holden remains eager to tackle new trends in patient care. First on the list? Precision medicine—the customization of treatment based on a patient’s unique tumor biology—which is poised to revolutionize clinical practice. While exciting, precision medicine represents a new paradigm for cancer care that will require both a new language and a new way of framing clinical evaluations. “There are many new questions that I’ve never considered,” says Dr. Holden. “Such as, how do I incorporate a genetic counselor into my practice?” And while it may take some time to fully realize the extent of its potential and deliver precision medicine to all men with prostate cancer, “it’s definitely the future,” says Dr. Holden.

Dr. Taplin is also optimistic for new developments in therapeutics—specifically, immunotherapies, advanced hormonal approaches, and other targeted therapies that could provide more effective treatment options for men with fewer side effects. She also believes that “liquid biopsies,” simple blood tests that can provide complete tumor DNA profiles, will obviate the need for invasive bone biopsies and bring us closer to true precision medicine.

Achieving these advances will see individual patients as the agents of change, with an increasingly central role in both treatment and scientific discovery. Dr. Taplin stresses the importance of participation in clinical trials in fast-forwarding new treatments and therapies to the clinic. Currently, “not everyone has access [to trials] but they are important to consider where available,” she said. Collaboration between doctors and patients to increase enrollment in clinical trials—especially as we learn more about the genomic complexity of the disease—will be key to realizing game-changing treatments that will benefit all men with prostate cancer.

With all of its promise, the future holds a degree of uncertainty, but both Drs. Holden and Taplin embrace what seems like endless possibility. “Staying abreast of science and understanding can be a burden, but it is rewarding, exciting, and keeps me engaged in a continuous learning process, which reinforces the satisfaction of being a physician/scientist,” said Dr. Holden. “It’s a joy, really.”

“In the old days, we had little to talk about,” says Dr. Holden. “Today we might ask, how do we use all the arrows in the quiver? That’s a good problem to have, and that’s what I tell patients.”