Believe it or not, there once was a time when the Grand Canyon was just a ditch. Before that, it was a rough patch in the desert with a river running through it. It took a very long time for that canyon to form, and the conditions had to be just right to allow water, blazing sun and wind to chip away through layers of fragile rock.

On a very much smaller scale, this is what happens to cause cancer when the conditions are just right.

Now, if you will: While we’re thinking about the Grand Canyon, let’s pan the camera a few miles away. We’re near some tall pine trees, and there’s a campfire. Some cowboys are sitting around it. Let’s imagine that they all have white hats; they’re good guys.

If you’ve ever sat around a fire, you know that wood sometimes pops unexpectedly and sends out sparks. That’s exactly what happens at our little campfire, and it happens to hit one of the cowboys square on the arm. He brushes out the sparks, then goes back to his seat. Nothing’s really changed; he laughs it off.

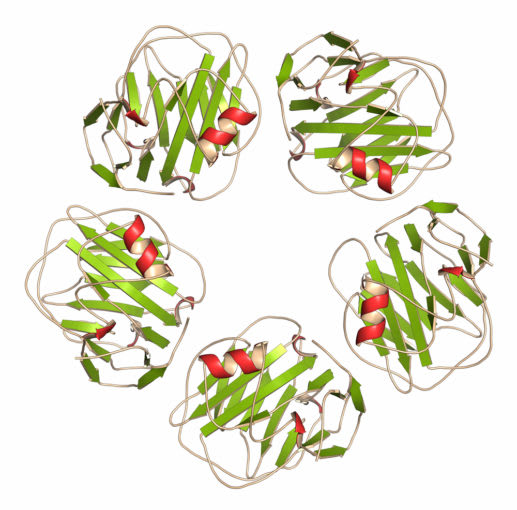

C-reactive protein

Wouldn’t you know it, the fire sparks up again – right on that same poor guy. This time, he’s a little more scorched; his shirt has a hole in it and his eyebrows got singed. He’s also a little irritated.

It happens a few more times, and he is no longer the proverbial happy camper. He’s moving around, no longer sitting quietly, he’s got some burns that will leave scars, and he’s angry. His hat is so charred now that it’s almost black. One last spark, and he’s out of there. He leaves the campfire, saddles up his horse, and rides away, fighting mad and looking for trouble.

This little scene plays out a lot, every day, in our bodies. There are countless campfires – like stars dotting the sky – that flare up, burn quietly, get snuffed out, and never cause harm. The campfires are little flares of inflammation.

Inflammation is our own version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: When it works the way it’s supposed to – when you skin your knee or get a paper cut on your finger, for instance – inflammation is what protects your body from bacteria and germs that find their way through the open wound. The immune system kicks in; zealous home soldiers spray chemicals on the intruders, puncture their armor, or even eat them whole. You notice some redness, a little heat, maybe some swelling or even a bruise, and you know that your body is healing. There’s a scab, new skin covering the hole or tear, and all is well. The inflammation goes away.

But what if it doesn’t go away? Here’s where the dark side of Dr. Jekyll, his alter ego Mr. Hyde, starts to show itself. Chronic inflammation is bad.

“The story of inflammation is absolutely the heart of what causes prostate cancer,” says oncologist Jonathan Simons, M.D., CEO of the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

“Inflammation lowers your defenses,” and changes the DNA. Going back to the angry cowboy at our campfire scene: If only he had moved away from the fire, or if someone had poured a little water on the fire to cool it down and keep the flames low. He might have had a few scars, but he would have been okay. Instead, he began moving around, and eventually he left the campsite; if he were a prostate cell, he would have become cancerous – but still there at the site, still easily treatable. But as he became more scorched, he became metastatic. The continued exposure to those flames turned him from a cell sitting quietly into a metastatic cancer cell.

Says Simons: “We estimate that 30 percent of all cancers are caused by this kind of chemistry.” The little fires hurt genes that are fire retardants, so the flames burn hotter; the fires then go after the fire fighters – so they don’t come and stop the burning. They don’t allow paramedics to come and heal the injured victims. The inflammation calls other cells called macrophages and granulocytes to the scene; they’re supposed to be part of the body’s cleanup crew. “Unfortunately, in cleaning up, they actually make the flames burn hotter and further damage the area.”

What causes the fires?

One huge cause is our diet. Fat, charred meat, processed carbohydrates, chemicals in junk food, and sugar. Basically, what we know as the Western diet – high in meat and bad carbs, low in fruits and vegetables. How do we know this? Because the men in the entire world least likely to get prostate cancer are men in rural Asia, who eat the traditional Eastern diet – low in meat, high in fruits and vegetables, with hardly any processed carbs. No soda, lots of green tea. No fries, lots of rice. No burgers, lots of broccoli.

“The rural Asian diet is anti-inflammatory,” says Simons. “It may be that these men would eventually develop prostate cancer if they lived to be 120. But they don’t.” If you think about our campfire analogy, maybe cells still get singed, but they’re few and far between. That critical momentum never develops.

“We are now learning that it’s essential for men to have a healthy diet when they’re young – say, between 14 and 30.” But men of any age can benefit from turning down the inflammation with “fire-fighting” foods.

The opposite is also true: Obesity and one of its consequences, diabetes, make these flames burn even higher. “If you are even overweight or borderline diabetic, you turn on more insulin to try to control your blood sugar,” says Simons. Insulin causes the secretion of molecules called cytokines, which – thinking of our cowboys at the campfire – are like the chuck wagon, bringing in oxygen, new blood vessels and nutrients to feed the cancer.

“You can reduce your insulin level with exercise,” says Simons. “There’s a lot of evidence that just being sedentary is a terrible setup for trouble later, if you have a slightly inflamed prostate and higher insulin level.”

The prostate is particularly vulnerable to this activity, Simons adds, because it’s just chock full of inflammatory cells called prostaglandins, most likely nature’s way of protecting the fluid that makes up semen. So the prostate is already a tinder box.

What else makes it worse? Infection. Cigarette smoking.

Okay, then what puts out the fires?

We’re still figuring this out. A good diet, exercise, and other flame retardants such as Vitamin D. Dietary supplements such as turmeric seem to help, as do broccoli and tomatoes.

And finally, there’s a huge question mark. What else helps? “This area of research is woefully underfunded,” says Simons. There may be a bacterial equivalent of H. pylori – the nasty bacteria found to cause stomach ulcers. New research suggests that probiotics – “good” bacteria that change the microflora in the gut – may prove helpful in preventing cancer. Does this mean that there are bad bacteria that do their share of causing it? Could this be related to the link between infection and inflammation?

We don’t know. Stay tuned.