A recent study funded by the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) reports a new strategy for “fine-tuning” how the body processes abiraterone to optimize therapy for men with metastatic, treatment-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). These exciting results were published in the May 26 issue ofNature.

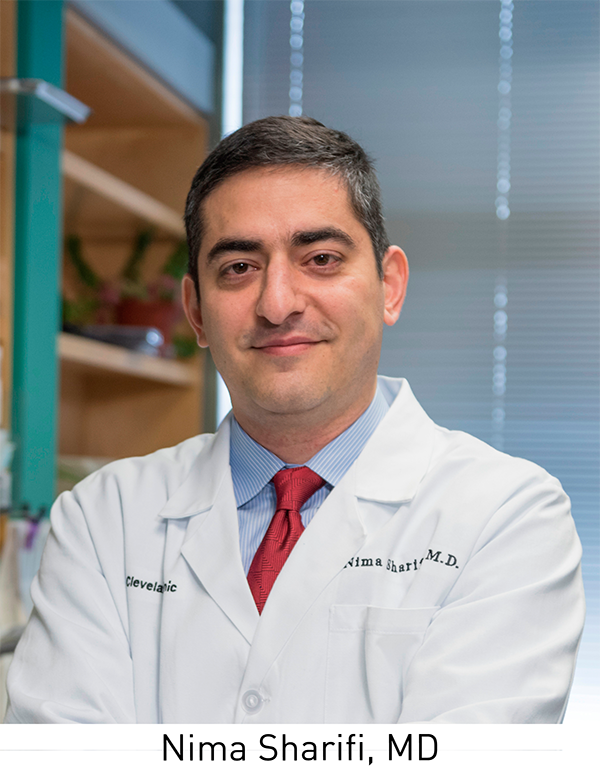

“Overall, our findings shed light into new and previously unanticipated aspects of how abiraterone is processed into other ‘good’ and ‘bad’ chemical compounds in the body when patients are treated on this drug,” said Nima Sharifi, MD, Kendrick Family Endowed Chair for Prostate Cancer Research at the Cleveland Clinic and the study’s senior author. “We have also devised a way to alter metabolism and allow the body to make less of the ‘bad’ and more of the ‘good’ compounds.”

“Sharifi’s discovery is a Tour de Force of team science in prostate cancer because of its Sherlock Holmes level of molecular biology, endocrinology and biochemistry detective work, and real-time monitoring of patient sensitivity to abiraterone,” said Jonathan W. Simons, MD, president and CEO of PCF. “Delta 4 abiraterone (D4A) rational therapeutics opens up a promising new chapter for expanding the length and duration of remissions by interdicting against intratumoral androgen production in advanced prostate cancer.”

While many research teams focus on discovering new treatments for diseases, finding ways to make existing drugs—the end result of years of research, development, and resources—work better for patients is a major priority in cancer research. Improving the efficacy of existing therapies holds enormous near-term potential for patients, who do not have years to wait for new drugs to come to market.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the standard, first-line treatment for men whose tumors have metastasized beyond the prostate. By inhibiting male hormones (androgens), ADT starves tumors of the fuel they need to grow and progress. While metastatic prostate cancer generally responds initially to treatment, most patients ultimately develop resistance to ADT. Few options for treatment remain following the onset of resistance, and this late stage of the disease, known as mCRPC, is associated with significant pain, suffering, and generally poor outcomes.

For this reason, identifying ways to better manage mCRPC in the long-term is an urgent clinical need. Abiraterone (Zytiga®) is a next-generation androgen inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2011 for the treatment of mCRPC. The medication works by blocking the production of androgens and is effective even in patients who have previously received chemotherapy. While abiraterone is effective in prolonging the lives of men with mCRPC, patients ultimately develop resistance and experience disease progression.

Importantly, abiraterone is a steroidal drug, meaning that it is similar in structure to the androgens that it inhibits, specifically testosterone. Last year, Sharifi and his team determined that after a tablet of abiraterone is ingested, much of it is converted into a compound (a metabolite) called D4A, which has even greater anti-tumor activity than abiraterone.

However, the chemical structure of D4A makes it susceptible to further alterations by enzymes that normally process steroids. This makes it difficult to harness the tumor-fighting potential of D4A in any meaningful way. It also raised important questions regarding the role that D4A and other metabolites play in patient response or resistance to abiraterone.

In the current study, the team showed that D4A is further broken down into a compound called 5α-Abi, a metabolite that, ironically, promotes prostate cancer progression. Based on this observation, they hypothesized that the efficacy of abiraterone could be improved by “fine-tuning” its metabolism to block conversion to the “bad” 5α-Abi and promote the accumulation of “good” D4A.

The team then tested this idea in a clinical trial that combined abiraterone with another medication called dutasteride, which is an inhibitor of the enzyme that converts D4A into 5α-Abi. They discovered that adding dutasteride to abiraterone allowed for the accumulation of D4A to higher therapeutic levels by preventing its transformation into 5α-Abi.

“We are basically damming up the river,” said Sharifi. “With the addition of dutasteride, we see significantly more anti-tumor D4A and much less of the negative downstream compound.”

These findings hold enormous potential for changing the way abiraterone is prescribed to patients. While more work is needed to determine the ultimate clinical effect of biochemically altering abiraterone metabolism in this way, the team has identified a promising new combination therapy that stands to improve the care of men with mCRPC.

Sharifi credits PCF with helping to establish the collaborative working relationships that realized these important results. In 2011, a team led by Steven Balk, MD, PhD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) and Peter Nelson, MD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) received a Movember – PCF Challenge Award to study mechanisms of abiraterone resistance in mCRPC patients, which included a clinical trial led by Mary-Ellen Taplin, MD of Dana-Faber Cancer Institute. As part of his site visit with the Balk-Nelson team, PCF’s Chief Science Officer, Howard Soule, PhD invited Dr. Sharifi—a 2008 PCF Young Investigator—to present his work on steroid metabolism and androgen receptor function. This meeting sparked collaboration across the institutions that culminated in a $1 million PCF Challenge Award for Dr. Sharifi in 2014. Sharifi is also the mentor of PCF Young Investigator Zhenfei Li, PhD, who is the study’s lead author.

“PCF introduced me to working relationships that had been going on for years. If you have that kind of relationship, it makes research so much easier,” said Sharifi. “Had Howard not taken me to that initial meeting, this collaboration—this project—would not have been possible.”